Last week I expanded on the conventional venture capital wisdom related to the avoidance of too many bad lots (investment targets) in the bucket. The standard recipe to avoid these odds (apart from engaging in thorough due diligences) is to invest in a sufficient number of start-ups. Conventional VC wisdom has it that one needs to invest in at least three distinct entities to arrive at a 50 per cent probability of at least one “success” and into at least 20 targets to arrive at a likelihood approximating 100 percent of at least one “successful” target. The same wisdom has it that out of three start-up investment one will go completely down the drain, one will at least give the money back and one will “succeed”.

I pointed out, that this wisdom is both empirically false and practically meaningless.

It is false because stats of American VC investments show a marked different picture. I had quoted the American VC http://correlationvc.com/ as one of several sources. In a survey covering the years 2014-2015 and 21,000 American start-up investments Correlation showed that two out of three investments just returned a multiple of 0-1. The same survey shows that only 10 percent generated a return higher than 5 (1.5 out of those with a multiple > 20).

But unfortunately, the wisdom is not just false, but also meaningless. It is meaningless, because “successful” is a vapid concept if “success” is meant to qualify one specific start-up in splendid isolation from the rest of a particular portfolio and its targeted return. If, e.g. one exit allows a portfolio to achieve an IRR of, say 36%, and this portfolio without that exit (and the corresponding target) would merely have achieved 20%, I daresay it is a very successful target. Does this mean that all “successful” start-ups need to give me that very return? Obviously not.

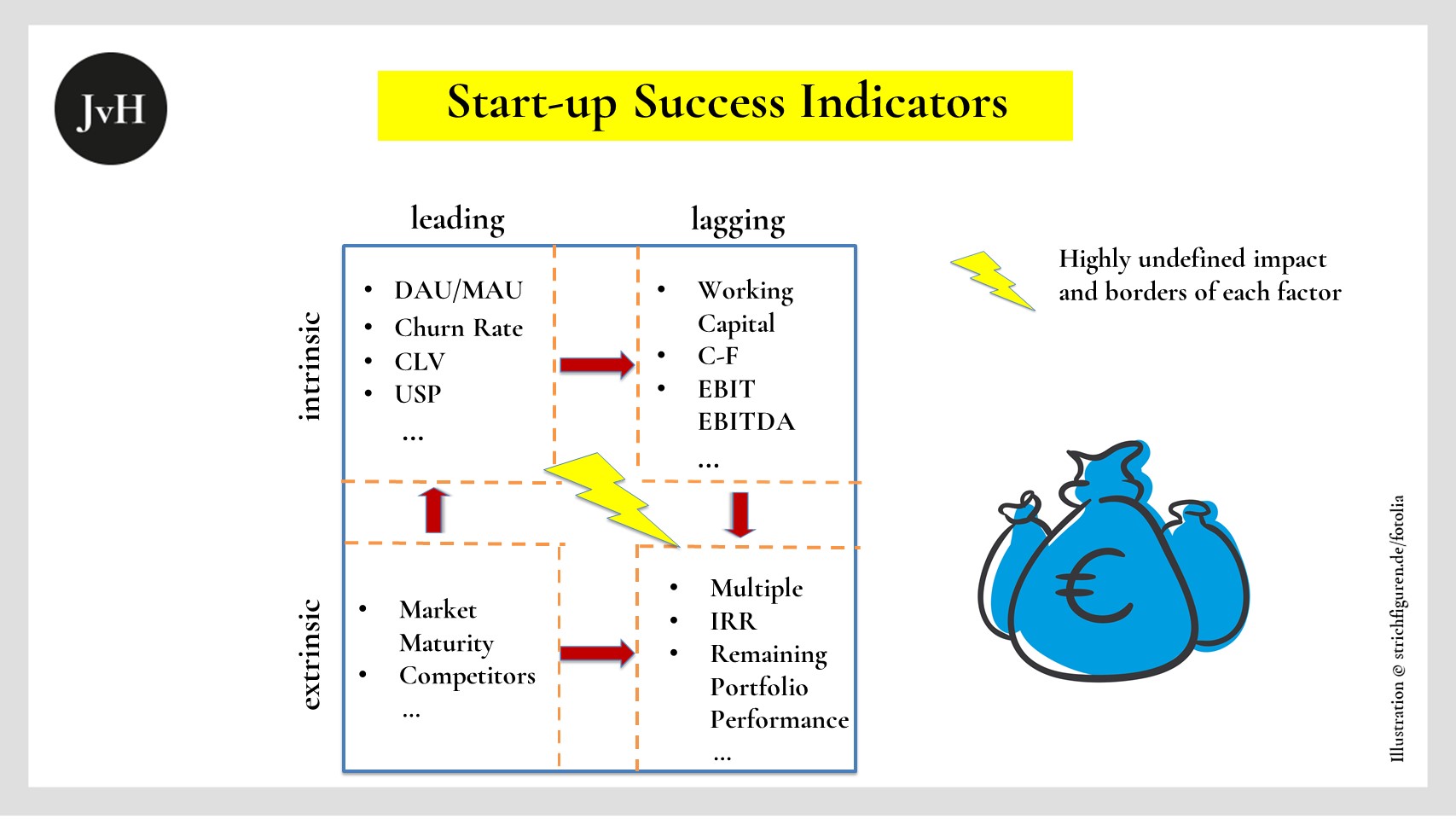

If, however, “successful” is indeed understood to mean that such a start-up or its exit helps a portfolio achieve its target returns the concept is empty. It remains empty because it does not distinguish between intrinsic qualities which are specific to the respective entity and extrinsic features which are related to the expectations of the market and the stakeholders. For instance, the multiple or IRR generated might be a stroke of luck, the result of another bubble in the market or whatever lucky “feat”.

To use a term from the Balanced Scorecard: In venture capital it seems there simply is no sufficient connection between “lead indicators” (intrinsic features of a start-up like processes, team, product) and resulting “lag indicators” (properties like cash-flow, working capital, return, prospective multiples). The latter largely depend on both, the mentioned intrinsic features and extrinsic circumstances pertaining to more or less accidental extrinsic circumstances. Thus, despite all the efforts to put some science behind investing in start-ups, the venture capital game appears to remain quite a gamble.

We face a dilemma:

Either we qualify a start-up by intrinsic features which have no direct (incontestable) connection to an investors’ and his or her LPs’ quantitative performance criteria (IRR, multiple etc.) or we qualify it by these very extrinsic stakeholders’ expectation criteria which will not allow us to assess – in time -if a start-up will help the fund meet its financial targets.

More on this next week.