In my last two (English) blog posts (part 1 + part 2) on the similarities and dissimilarities characteristic for VC and angel investments, we obtained the following preliminary results:

- Neither VCs nor angels seek risk diversification. (Part 1)

- Irrespective of both VCs and angels not wanting to diversify, they also cannot do it, i.e. even if they wanted to. (Part 2)

- The principle reason for this is that you cannot classify start-ups in a meaningful way. They are subject to constant change and are not representative of their industry, their maturity stage and so on.

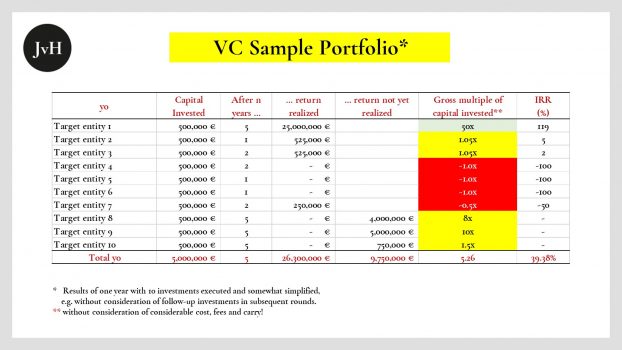

- Since venture capitalists need to achieve a certain minimum return to satisfy their LPs, they prefer to invest in start-ups that at least have the potential to offer an extreme return. This extreme return, say a multiple of >100 within x years for fund a or >50 within y years for fund b, is required to overcompensate the losses obtained from the remaining flopped investments.

- In order to obtain such outlier VC fund trophies, VCs have no choice but to make do with the “serious flaws” as discerned by Marc Andreessen as an almost inevitable feature of “the companies with the real extreme strength”. It does not matter, if 9 out of 10 investments flop, if the tenth evolves as a stellar success.

Only one question now remains: Do the last two above issues (4. and 5.) apply to VCs only, or do they also apply to business angel investments?

Beyond the investment sum, which is usually higher for VCs than for angels, there are other characteristic differentiators between the two. Here, I do not mean differentiators to be found when you look at angels driven by very personal motives such as charity, some idiosyncrasy, or some other biographic motive.

Rather, I am concerned with the “Muster-Tech-VC” and “Muster-angel”, i.e. investors who select their target objects exclusively from a reasonable business perspective. So, what is the fundamental difference between angels and VCs?

Deal flow: Angels do not need to document their quality choices

One obvious difference between the two is the respective portfolio size in terms of the number of the individual investments.

According to the German Business Angels Panel No. 66 (2nd quarter 2018) “the portfolio size has been constant for years. According to the panel, each angel is responsible for around six teams. However, the spread is large. At the lower end there are two investors, each concentrating on one investment. And at the top is a high-performance angel with 20 chicks under her wing.”

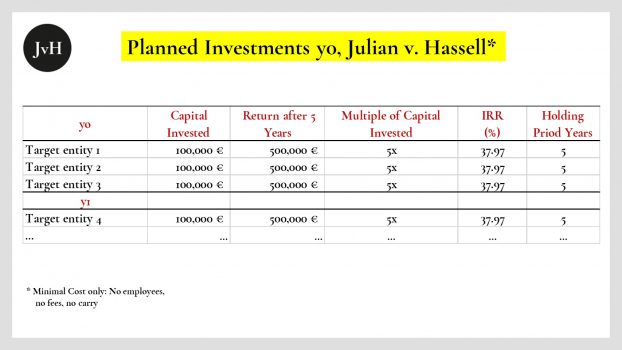

The median number of annual investments carried out by an angel will be roundabout three. That is also my number of annual investments.

But even more crucial than the number of funded entities is the number of start-ups which undergo screening.

Even if the partner of a VC fund was supposed to land three deals per year only, this partner’s team will need to have scrutinized at least 10 times as many target companies by means of due diligences or parts of it and it will have scouted at least 100 start-ups. This is the only way to show the care a VC has taken to invest in the best of the best, a requirement paramount to remain in high esteem withLPs, when fund KPIs look bleak, which the always do at times.

For a fund to be able to do this, it has to send a host of young “analysts”, venture partners, associated angels and so on hunting for target entities and ensure a permanently gushing “deal flow”. Business angels are not subject to deal flow pressure exerted by law or LPs. As a result, if we presuppose comparable gross returns as I have done in the two tables above, angels produce better net results. But there is more to it than just cost.

Quantity at the expense of quality

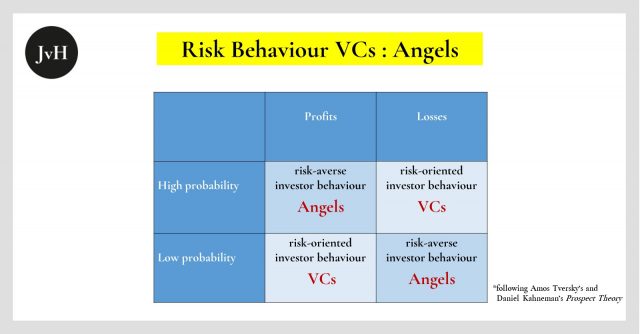

Large quantities of portfolio entities and portfolio prospects do not necessarily translate into excellent choices. Because angels invest their own money, angels are less frivolous with cash than VCs. Of course, I don’t mean to say VCs were frivolous. But they are more frivolous and actually need to be more frivolous to compensate the large quantity of flops which their investment philosophy necessarily entails. angels do not require phenomenal returns, if all or nearly all of their investment produce decent ones.

Different attitudes towards risk

At the entry stage of a VC acquisition funnel, you will usually find young analysts who recently graduated from some top university, but who have little or no operative experience of their own with the ardour and difficulties that inevitably go along a start-up founding process. These young employees need to make a name for themselves. And the best way to do this is through generated output and stunning pitch decks. Phenomenal returns is not an issue, as returns won’t show up before, say 5 to 7 or even more years. By that time, the analysts expect to have reached managerial, if not partner level.

One could thus argue that analysts in VC companies are similarly risk-averse as business angels. However, the risks and opportunities for VCs and angels relate to completely different phenomena: Here, we have the analyst concern of missing the criteria as defined by VC partners, there we find the angel concern of a most painful loss of her or his own money.

Quantity obscures quality

So, how do VC analysts demonstrate “performance” and how do VC partners show potential fund performance to colleagues and LPs without having to resort to history? They show quantity. Their situation resembles any standard sales organization: “In order to acquire x clients, I need to screen y leads; to be able to scrutineer y leads, I need to have made contacts to z potential leads. How these contact stages: client/ customer, lead, potential lead, i.e. mere contact, are defined, is hardly ever defined unambiguously – neither in sales organisations, nor in VCs. If you take two young analysts, say analyst a and analyst b, both will be briefed in a different way respectively by their respective partners c and d.

Therefore, what you usually encounter in a VC fund management organisation are hard formal fund criteria such as branch, business model, start-up stage, money requirements etc., but no criteria relating to their respective quality. As a matter of fact, such hard quality criteria cannot possibly exist for them as we have learned from Marc Andreessen that the companies “with the really serious strengths” are those with the “really serious flaws”. If the acquisition funnel were to filter out these major weaknesses, “star acquisitions” who turn a fund into a winner and give the fund management a fair amount of money above the hurdle rate, would never enter into that fund.

Angels screen better

As a result, it is not much more than simple, arbitrary luck, whether and to what extent a VC fund finances stars or losers. Often, partners reach a consensual agreement as set out in their GP rules. The lucky start-ups then perhaps had a good day and presented well or the partners were in a particularly good mood or whatever. True, some funds have a better track record then others. Yet: the same rule applies to GPs and start-ups: Their own history does not allow for meaningful judgements on their respective future.

You may now object: “Fine. But how the hell can angels possibly arrive at better target entities? They obviously need to choose as well? How on earth do they do their individual micro job – target by target – in a manner that differs from that of VCs? Well here we come back the issues I have just touched already:

No dry powder pressures

angels don’t have to invest. They want to invest. They don’t need to document their track record to LPs. They do not need long-listing or short-listing

No “unicorn” pressure

As mentioned already a number of times, a16z’s Marc Andreessen noted, the companies with the really serious strengths were also those with the really serious flaws. angels do not need to aim for the 100 x multiples or the unicorns, if they exclude the serious flaws from their acquisition funnel. Would that in turn mean, that they regularly arrive at just mediocre start-ups and returns? Maybe. But so, what? Compare an IRR of my 38 % to the average IRRs you earn with other alternative assets. They are no better. They are worse. Mediocrity is a modest price for passing on the bad risks to VCs, if mediocrity amounts to an IRR of 38 percent?

Better shortlisting

Due to their own entrepreneurial, if not start-up biographies, angels are doing better at shortlisting than VCs. Many of them benefit from their personal background as (serial) entrepreneurs and founders. You will always find exceptions, but in general, an angel’s acquisition funnel manages to select far more effectively and efficiently at the funnel’s entry level than a VC funnel. This first hurdle is the most important of them all. The further down the funnel one goes, the more homogenous it becomes: The deal – no deal issue at the end of the funnel is not a start-up quality issue, but a deal quality issue. The start-up quality quest is resolved at the funnel entry level: If, at this stage, the pre-selection of potential target entities is incomplete or severely flawed, the final selection made by the fund partners will result as the choice of the least “rotten” apples at best.

Better selection criteria

The really dominant criterion on the basis of which angels make up their minds is the management capability of the founders. While VCs pre-select on the grounds of company age, capital requirements, industry, business model, business plan, etc. VCs check the management quality. Some VCs, surprisingly also Andreessen Horowitz, claim that other success criteria, such as the Product Market Fit (PMF), were more important. They argue, a manager may always be replaced by another. Frankly, I find this bizarre. Every VC and every angel I know, knows for sure that at an early stage, start-ups will have to continuously adapt their business models. They need to do so just in time. To be able to cope with rapid change, you need determined, but flexible, strong but socially competent, intelligent but modest founders. These founders need to be ready to test their products, services and technology and they need to be honest to themselves and not betray themselves and their investors when realizing that they need to pivot. Of course, PMF is important. But whether a product is fit for the market or not you will always find out in retrospect only. To be able to test in due time and draw the right conclusions and to be able to also carry them out you need what? Right, you need the excellent founders! Good angels detect good founders so easily because their own professional life is rich in good and also not-so-good experiences. They also sense and feel the atmosphere within a start-up at once and draw their conclusions from there.

Exclusiveness unwanted and unneeded

Finally, business angels are not interested in keeping their investments exclusive to themselves. On the contrary, they require co-investors, further angels and also VCs to be of relevance to their chosen start-ups. True, VCs frequently syndicate their investments as well. But most privately managed funds wish to handle a financing round either as lead investor or as an exclusive investor. VCs with more flexibility in this regard will anyhow carry certain reservations vis à vis certain other VCs. This reduces the number of good deals available for VCs and increases those available for angels.

Apologies/ Conclusion

My last three English blog posts were aimed at examining the major similarities and dissimilarities between angels’ and VCs’ target recruiting processes and considerations. I am aware that meaningful general observations come at the expense of doing injustice to individual cases. I therefore apologize to those VCs, who employ different strategies and methods from those described above. On this note I wish to conclude this series. My next post will highlight some major weaknesses that go along with the angel strengths described in this post.